Kapālakuruṇṭaka’s Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati

Āsana Sequence Reconstruction

musings by Philippa Asher

the above image tāṇḍavāsana (Śiva’s dance pose) is from the film entitled ‘Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati: A Precursor of Modern Yoga’

Yoga practitioner: Philippa Asher Film Director: Jacqueline Hargreaves © 2018

ekena pādena sthātavyam utthātavyaṃ tāṇḍavāsanaṃ bhavati

[The yogi] should stand on one leg and raise [the other. This] is [Śiva’s] Tāṇḍava-dance pose.

Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati āsana description number 80

(translated by Jason Birch in 2013), published in ‘The Proliferation of Āsana-s in Late Mediaeval Yoga Texts’ (2018)

The Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati is one of ten Sanskrit texts critically edited and translated as part of the Haṭha Yoga Project at SOAS, University of London. Led by Dr Jim Mallinson, with Dr Mark Singleton, Dr Jason Birch (and others) between 2015 and 2020, the Haṭha Yoga Project charts the history of physical yoga practice using philology and ethnography.

It was a great honour to be involved with the reconstruction and filming of āsanas from the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati, which (as well as giving instruction on other aspects of the practise of haṭha yoga) describes 112 postures that are divided into six groups, possibly sequences:

Supine (1 to 22)

physical culture exercises and yoga āsanas where the chest, hips, shoulders or face are generally upwards and often with part of the back on the ground

Prone (23 to 47)

movements and poses that mimic things in nature, where the hips, belly and gaze are generally downwards

Stationary (48 to 74)

familiar and recherché āsanas (many of which are quite complicated) that are generally held on one spot

Standing (75 to 93)

dance movements, obscure physical culture gestures and complex āsanas that are generally performed in an upright position

Postures with Ropes (94 to 103)

elaborate methods of climbing, ascending and balancing on rope

Postures which Pierce the Sun and Moon (104 to 112)

advanced yoga āsanas that are recognisable in today’s modern postal yoga practice

Experience of practising the Haṭhābhyāsapddhati postures

To play around with such an atypical selection of āsanas and to move in a completely new way was enormous fun and quite a challenge given that I had about eight weeks to study and figure out over a hundred postures, from a transliterated and then translated 18th century Sanskrit manuscript. As a comparison my daily āsana practice (which I have been doing since the late 1990s), is the Ashtanga vinyāsa method. It took fifteen years for me to learn/master the Primary, Intermediate Advanced A and Advanced B Series directly from my teachers in India (that’s around two hundred āsanas), perfecting one posture, before learning the next – so the process was completely different. It is also important to note that specific Sanskrit āsana names aren’t necessarily understood to represent the same postures in all haṭha yoga traditions. Names and āsanas can vary considerably.

Obviously without having a strong daily āsana practice and years of experience with postures on a deep level, it would be tricky to fathom the āsanas in the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati, let alone do them. Some are quite complicated, others are simply movements that I’ve never needed to do before and some are influenced by physical culture, gymnastics, martial arts and dance. Having a more sophisticated understanding of āsanas, how to perform them and indeed express them within logical sequences, makes the intelligent guess work that is involved when reconstructing from a page, more likely to be accurate.

Experimenting with the diverse range of postures described in the text and observing similarities and differences between what we consider to be āsana today is deeply fascinating. A few of the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati postures focus on strength, others on flexibility or balance and then there are obscure āsanas such as the curlew pose (103) which I interpreted as: whilst squatting, hold a stone weight with the teeth, loop your arms behind the calves and squeeze the outer shins with the forearms, place a vertical rope in each fist and then climb up said ropes). Also the polestar (89) in the standing section, might not seem out of place in a 1830s Parisian can-can dance performance. Encouragingly several poses described in the text, have evolved into postures that are part of today’s Ashtanga Primary, Intermediate, Advanced A, B and C āsana Series (and probably other posture-based systems too).

Having studied dance anthropology, history and performance at university, I found the eclectic element of the sequences intriguing. Given that some descriptions suggest movements that don’t seem like āsanas at all, it begs the question when does a movement become an āsana? For me it is when there is perfect synchronisation of breath, movement and gaze point, the physical alignment is perfectly at ease (allowing free-flow of prāṇā) and there is stillness of the mind. With this in mind and given that I have encountered several agile adolescents across India who could demonstrate the shapes described in the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati with ease, I wonder if executing a posture when concentration, breathing, technique and state of mind are less steady, is better described as exercise (rather than haṭhā yoga)?

Approach to learning the Haṭhābhyāsapddhati postures

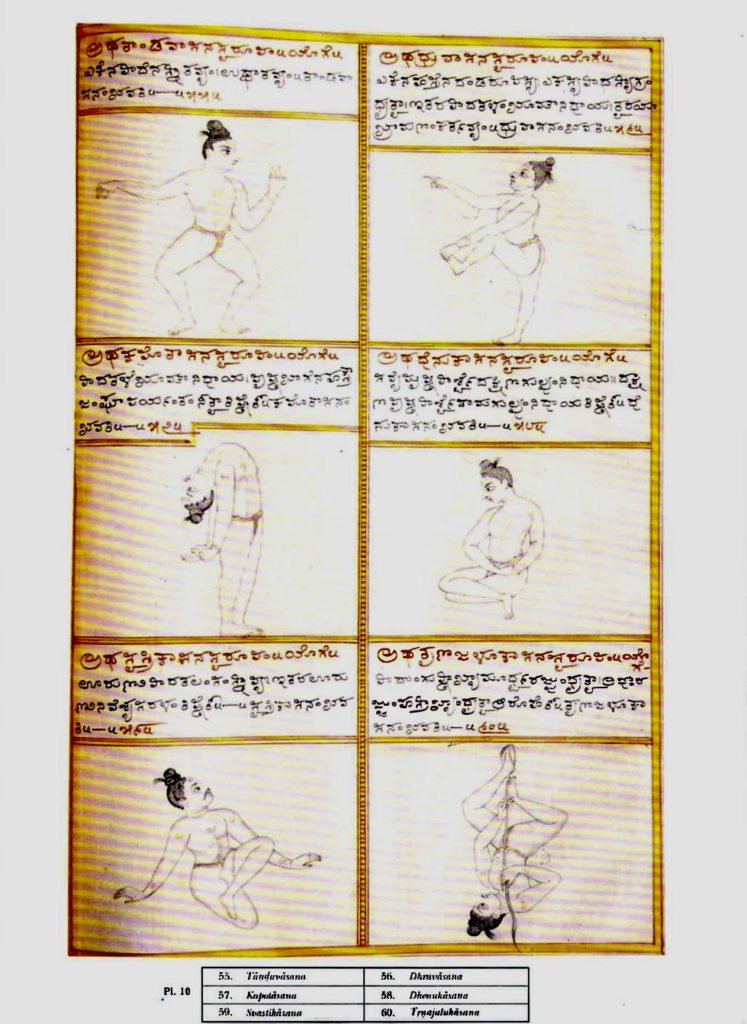

I spent a lot of time studying the translated textual descriptions of the āsanas, then worked out how they could be transferred to the physical body. I tried to avoid being influenced by the illustrations in the Śrītattvanidhi, as there’s a lot of artistic licence in the drawings (which seemed to be morphed to fit tidily into boxes with disproportionate body parts). Some depictions involve defying gravity and dislocating joints and none of the illustrations indicate where the floor should be. I’m not sure how helpful they are, but as art, are wonderfully enthralling.

So I played around with each āsana of each section (one by one) and then flowed them together as a dynamic sequence. After working out all sections, I then practised each from start to finish (as described in the text): supine, prone, stationary, standing, (I didn’t have access to a vertical rope), those that pierce the sun and moon.

Performing all sequences consecutively was quite demanding (mainly because I was working in a new way and we only had eight weeks before filming). In the Ashtanga āsana system, one methodically perfects each posture before learning the next and only when this is synchronised with tristhāna, vinyāsa and safe physical alignment, does the practice become a moving meditation. It takes decades to experience this. Thus I felt it vital to learn, memorise and practise all sequences in the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati many times, in order, to feel the progression and flow of each section (and also to experience the counter poses and to understand how the postures work dynamically and energetically on the body, as well as with the mind and breath). Unfortunately without having a dangling rope to hand, I couldn’t play around with and feel the rope sequence, so had to mark the postures on the ground. I suspect these were influenced by movements from the Indian sport Mallakhamba and might have come in handy for climbing trees (or scaling walls during British Rule?)

The process for me was rather like lifting a piece of dance from a Benesh notation score (five line staves with bars, upon which movement is notated) … but without having the choreographer present, so there’s plenty of room for interpretation. I would suggest that if you give the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati āsana descriptions to six different experienced āsana practitioners, you would see six different expressions of each posture.

For example with Matsyendrapīṭhaṁ (105), the Sanskrit description when translated is curious, as it states that the left heel is on the navel and the right foot on the left thigh, but the right foot is also below the left knee (!) and that you clasp the outside of the right knee with the left hand and hold the toes of the left foot:

“Having put the left heel on the navel [and] the other foot on the [opposite] thigh, clasping the outside of the right knee with the left hand and holding the toes of the [right foot, which are] below the left knee, [the yogin] should remain [thus. This] is Matsyendra’s seat.”

It makes more sense (to me) as:

“Having put the left heel on the navel [and] the other foot OUTSIDE the [opposite] thigh, clasping the outside of the right knee AND with the left hand holding the toes of the [right foot, which are] below the left knee, [the yogin] should remain [thus. This] is Matsyendra’s seat.”

I went with the Ashtanga Advanced A Series’ pūrṇa matsyendrāsana, with my left foot in the navel, right foot on the floor outside the left leg and my left hand holding the right foot and right hand on my left thigh. Jason tweaked this, so my right hand was on the floor behind me (as in the Śrītattvanidhi illustration).

Another instance is tānāsana (112) which I interpreted as samakonāsana (side splits in the Ashtanga Advanced B āsana Series), but Jason thought it was literally just stretching the legs (as in after waking up) from the previous posture (śavāsana). Jason’s interpretation makes sense if the posture directly follows śavāsana, but the sentence ‘having stretched apart both legs’ makes me wonder otherwise. However if this is the case, why would it follow śavāsana? Could it be that ’stretching out the legs pose’ might actually have come before śukyāsanaṁ (110) ‘oyster pose’? As someone who practises ‘oyster pose’ regularly, or kandapīḍāsana as it is known in the Ashtanga Advanced C Series, I can share that the hips need to be incredibly open (accomplished through mastery of side splits). In the Ashtanga āsana system, samakonāsana is practised two āsanas before kandapīḍāsana.

Just one of the many absorbing questions that this type of reconstruction invites …

Challenges and differences compared with my daily āsana practice

On a practical level, I’m a forty-something year old Western female, trying to make sense of a transliterated and translated text, probably composed by an Indian male a couple of hundred years ago, in a context and culture that is very different from mine. I have also observed over the twenty years that I’ve spent living in South India and learning yoga from gurus there, that the way of expressing things in their language is very different from mine. Thus when lifting an āsana from an Indian text, I would suggest that maybe taking each word literally and then translating it as it is, might not always be what the authour/teacher/practitioner is attempting to convey? Perhaps there are challenges when using Sanskrit vocabulary to describe movement? A further example is the description/translation for krauñcāsana (103): ‘having passed the fists through the thighs and knees’, obviously you can’t literally do that.

The text offers very limited information on the postures, which raises the following questions for me:

* Was the text actually written down by the visionary behind the sequences, or even by an accomplished āsana practitioner?

* Is the numbering within the sequences/order of the āsanas reliable?

* Are the descriptions of how to execute each individual āsana accurate?

* It’s one thing to be able to proficiently demonstrate an āsana, but it is another skill entirely to eloquently and succinctly use precise vocabulary to describe how to perform a posture.

* Why is there no guidance on dṛṣṭi?

* How long are the postures meant to be held for?

* Do you perform certain āsanas on each side?

* Should you master one posture before learning the next?

* How would you practise: a separate section each day for six days, the whole thing daily, or are the sections for different practitioners? If so, for whom/why etc?

* Would women have learned/been taught these postures?

* Would the practitioner continue with these sequences during different life stages, or were they used in a bespoke manner as the individual matures?

* How does a pose ‘pierce the sun and moon’? What is this referring to?

* Would this be a solitary practice?

Experience of the Haṭhābhyāsapddhati āsana sequences as a practice

The sequences in their entirety are fun to practise and collectively invite equal levels of strength, flexibility, balance, stamina and concentration. However they are not as refined and elegant as those of the Ashtanga āsana system that I practise daily (which took Pattabhi Jois fifty years to perfect). I would need to practise the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati sequences for a long time to know whether they have the same effect mentally, physically and energetically as the Ashtanga āsana sequences: to see if it’s possible to reach the state of a moving meditation. Also, without being able to go back in time to experience first hand how the sequences described in the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati were taught/learned, we’ll never really know how they were practised.

It is of course wonderful to have access to an historical text that describes a wealth of āsanas in a potentially dynamic sequence, which includes several postures that appear in Krishnamacharya’s Yoga Makaranda, as well as many of those now the in Ashtanga āsana system of Pattabhi Jois (and other modern haṭha yoga methods).

It seems possible that if Krishnamacharya did have access to the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati, the Śrītattvanidhi and other movement works, he was likely to have been inspired by them and consequently these absorbing texts have probably shaped many of today’s modern postural yoga practices.

© 2020 Philippa Asher

above is an example of āsana illustrations from the 19th century South Indian iconographic treatise the Śrītattvanidhi, published in Norman Sjoman’s ‘The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace’ (1996)

top left (55) shows the artist’s impression of tāṇḍavāsana

‘Stand on the foot with the other raised. This is tāṇḍavāsana, the āsana of the fierce dance of Śiva.’