Musings About an Ashtanga Asana Practice from Twenty-something to Forty-something

Ashtanga and Ageing

by Philippa Asher

The Ashtanga yoga system can spark a magical period in one’s twenties and thirties. Without even noticing, our lifestyle can change and the courage to rework aspects of our life that are no longer us, can manifest.

I discovered the Ashtanga practice in my late twenties. It was incredible. It still is. For me, the asana limb was a healthy replacement for dance. I trained as a ballet dancer and taught for the education departments of a couple of British ballet companies, after completing my post graduate degree in teaching adults, at university.

What I loved most about the asana system, was that in the 1990s, it didn’t seem to be at all competitive and you could be any shape, size or age to enjoy it. You just had to make an effort to show up to class (which for a twenty-something in London back then, wasn’t easy). It was the euphoria that I felt when taking rest, that was so amazing. I started off going to led-classes. I decided that if I could ever master Supta Kurmasana, I would stop. It seemed like such an unachievable goal, but gave my mind something to aspire to. It wasn’t long before I got the bug and one class a week, turned into two and then ‘guided self-practice’. I was was fairly supple from having been a dancer, but lacked adequate shoulder and arm strength. I worked hard to correct the imbalance in my body and my mind discovered a whole new level of determination and drive.

Guruji spoke about learning the practice slowly and with good reason. I moved through the Primary and Intermediate Series fairly quickly and it wasn’t long before I encountered the Advanced A Series arm balances. The way my body dealt with the additional weight-bearing on a non weight-bearing joint, was to increase the bone density in my wrists. This sounds great, but the extra jagged bone managed to saw through the tendon that works the thumb, in my left hand. I had a tendon graft and then two years later, snapped the same tendon in my right wrist. A wise person would have taken a decent about of time off the asana practice, to allow the graft to settle and for the trauma to recover. I was young and foolish and was swinging around on my plaster of Paris cast, the next day. I had my second graft in Mysore and managed to bust my stitches during practice (no cast, just a bandage this time). The surgeon sewed me up with no aesthetic, to teach me a lesson. It took another decade for me to actually learn from the experience.

It is well documented that when Krishnamacharya was teaching at the Jaganmohan Palace in the 1930s, most of his students were young, agile males. The asanas and vinyasas that he shared, were athletic and almost gymnastic. In those days, Krishnamacharya said that his classes were not for women. It was only when Indra Devi persuaded the Maharaja of Mysore to intervene, that Krishnamacharya had his first female Western student. Devi was said to have been taught in a more gentle fashion to the men and subsequently shared asana in the West, without vinyasa.

Guruji of course, was one of those young agile boys and went on to become a long-term student of Krishnamacharya’s. If he was still with us, I would ask Guruji how the Ashtanga asana practice felt in his body, as he progressed in years and whether he continued with the Advanced sequences, until he gave up his postural practice in the 1970s.

We know that the ‘series’ learned by Guruji’s first groups of Western students, developed into what they are today. His Laxmipuram shala was called the ‘Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute’, which suggests that the practice was still evolving. Women were (and still are) taught the same demanding sequences as men, despite having smaller frames and muscles. It would be interesting to know if Guruji’s long-term students (from over twenty to forty years ago), are still practising in the same way, or whether they have refined their practice, to adapt to their bodies maturing.

Learning asanas on a feminine body, is probably different to learning them on a masculine one. The quintessentially Indian male frame with its broad shoulders, long back and narrow hips, is perfect for the Ashtanga asana practice. I have narrow shoulders, substantial hips, long limbs and a small upper back. This is great for leg behind the head work, but not so beneficial for hand balancing (where shorter limbs, wide shoulders and a long trunk, are helpful). In order to build strength, I have had to practise, practise, practise.

I enjoyed many years of feeling invincible after my tendon grafts, but ‘overdoing it’ eventually caught up with me. Osteoarthritis is not uncommon for athletic women, when they reach their mid-forties. Worst affected are my wrists, from excessive weight-bearing; neck, from placing my feet on the floor in Ganda Bherundasana and big toe joints, from years of landing heavily in Chaturanga, on unsprung floors. I now work more intelligently with the practice. Swift Suryanamaskaras and vinyasas between sides and postures, compound my joint pain. Elongated breaths and steadiness of mind and body, are key to my staying healthy. Regular exercise is good for my osteoarthritis, but I have to be smart when assessing which asanas have become too extreme. Ahimsa (non-harming), is the first yama of the Ashtanga practice after all.

Also, the length of my practice in my late thirties was rather long. Before I was ‘spilt’ between Advanced A and B, it took nearly three hours and I did not have a ladies’ day in three years. I should have told my teacher, obviously. Ladies’ holidays are important and if women are not menstruating, they need to explore why and then address the problem. The practice is all about finding optimum spiritual, physical and mental well being. This is hard to achieve if the body is under nourished, or over driven. I now practise Ashtanga asana five days a week, for around two hours. If I push for a sixth day, my ladies’ days stop and my joints hurt. The traditional one rest day a week is fine for some people, but part of the practice is being able to listen to the body and to intuitively act intelligently.

Without question, the asana practice is extremely valuable and each sequence in the Ashtanga system, brings its own fascinating challenges. Some students go through an intense or aggressive phase when learning the Primary Series and others may become tearful during the Intermediate Series (body opening and nerve cleansing respectively). Advanced A is great, because by the time you have completed the Primary and Intermediate Series, you should have the strength, stamina, flexibility, concentration and emotional maturity, to explore the more lyrical and demanding poses. You just need a lot of energy and time in your day, to master them.

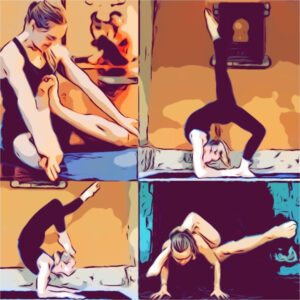

And then there’s Advanced B. This inspiring and strenuous series requires a whole new level of mind-power, one-pointed focus, determination, dedication, flexibility, strength and technique, to conquer the unachievable. It took me ten years to learn from Guruji and Sharath and I’ve never worked so hard to accomplish asana before. I would spend hours on my own, analysing the movement, breath and drishti of these complex postures, until I could make a semblance of the shape that I was aiming for. Then of course the asana has to be placed correctly within the context of the vinyasa sequence. The one saving grace is that the arrangement of Advanced B is more sustainable than A, as the postures are so varied in their order. Advanced A can be exhausting for someone with tiny shoulders, achy wrists and women’s hips, with its ten consecutive arm balances. The task is to find the equilibrium between the strong masculine, powerful athleticism that is needed and the graceful feminine, humble determination (the ‘pingala’ and the ‘ida’, or sun and moon qualities).

Growing older makes the asana practice even more interesting. On the one hand you become easy going and experienced, yet on the other you have to strive twice as hard, because everything requires more effort. For me, there’s the added challenge of working with osteoarthritis. I now have a thick mat, which acts as a shock absorber and I’m learning to be more mindful and gentle in my practice. I don’t put my feet on the floor in Ganda Bherundasana anymore. I could, but I choose not too. My ego still entices me to push to the limit, but wisdom now says ‘go to the point where you are steady and calm, you want your body to last a lifetime’.

It may be possible to sustain an Advanced B practice throughout one’s forties (when not teaching for several hours a day), but I’m guessing that with each subsequent half decade, one might be inclined to drop a series. That way, when we pass sixty, Yoga Chikitsa becomes the primary focus again. Of course our bodies, stamina, lifestyles and asana practices are all quite different, so it’s unlikely that there’s one answer for everyone.

I practise Ashtanga asana, because it makes me happy (as do the other limbs). The ‘series’ doesn’t matter. Ultimately it’s quality of intention, rather than quantity of poses that count. The asana practice is simply to lead us towards the higher aspects of yoga philosophy, so that we can access our true Self and be purified from the afflictions of our human condition. We’re aiming to radiate joy, modesty, generosity, honesty, wisdom, humility, contentment, peace and kindness – to be free from the clutches of material and emotional life. For some of us, travelling through several asana series and back again, might be requisite for our spiritual journey. Guruji shared however, that others might attain samadhi, by simply practising half Primary Series.

~ abridged version appeared in Pushpam magazine, Summer 2016

© 2016 Philippa Asher